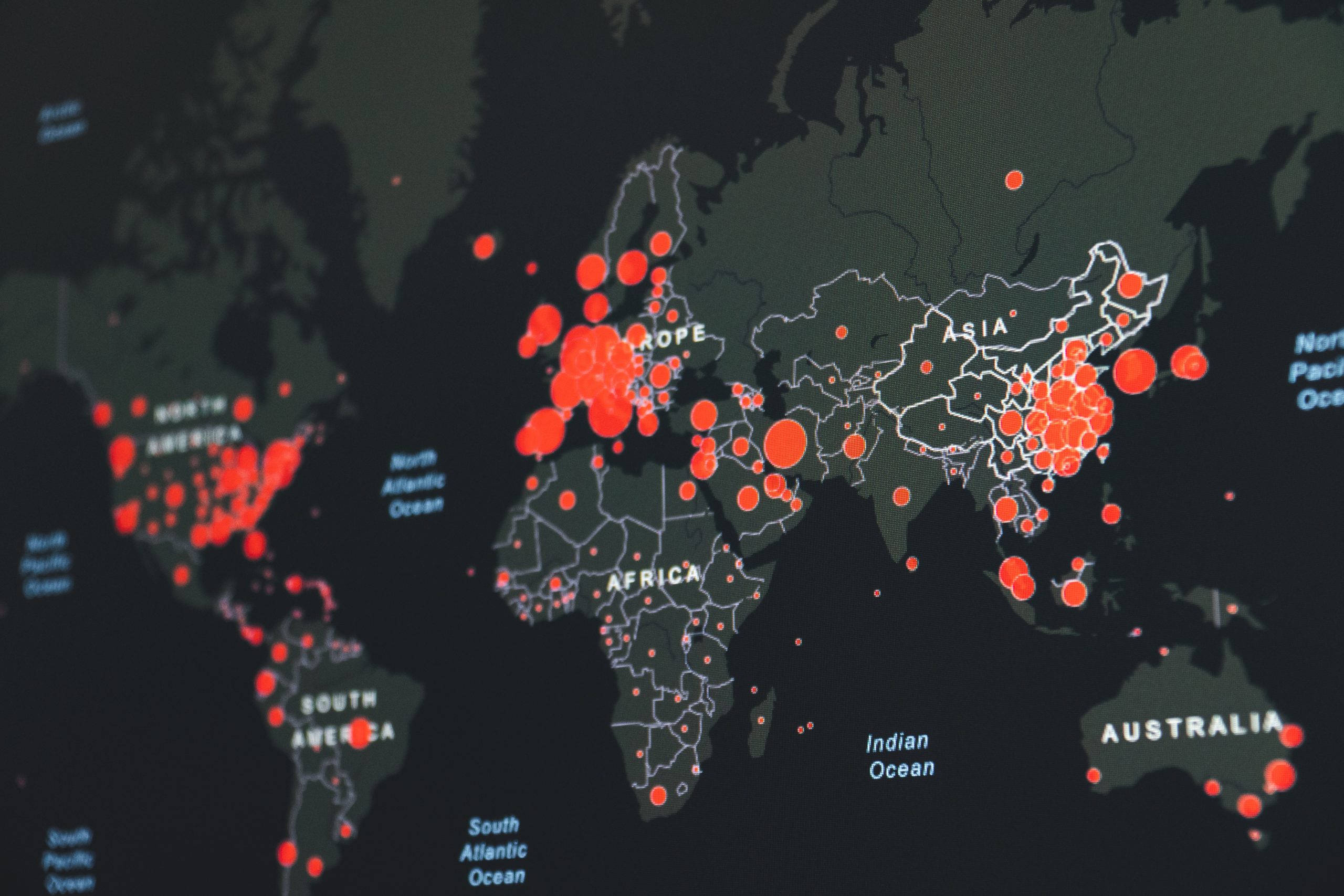

As of March 2020, the globe began a new dynamic, culminating in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) proclamation of the COVID-19 sickness as a worldwide pandemic.

The subsequent reactions to this event resulted in the closure of not only restaurants and hotels, which are important selling points for seafood products but also national and international markets, disrupting input supply and product placement for aquaculture and fisheries.

In 2020, 178 million tons of seafood products were acquired from fisheries and aquaculture worldwide, with a total first sale value of around USD 406 billion. That is a contraction of 1 million tons compared to what was produced in 2018. Even so, according to the FAO, this contraction was only observed in 2019 (-1% growth), with values of production recuperated by 2020 (+0.1% growth) and is expected to keep growing by 2021 and 2022, mainly thanks to aquaculture production.

According to the FAO, the real problem was not so much in the production side of the value chain (although it had some difficulties) but the disruptions throughout the supply chain in a highly globalized industry (remember that seafood is amongst the most traded products in the world, with a trade value of USD 164 billion in 2021, more than the added trade value of coffee, rice, wheat, corn, and poultry). Closure of borders impeding travel and the impossibility of visiting restaurants and hotels shifted the demand for seafood from these services to retail, causing severe disruption to the chain, the prices, and the structure of the aquaculture industry as a whole. This led to crowded cold storage facilities, severely overstocked inventory in the food services and significant understocking in normal retail markets (such as supermarkets).

As a result of these disruptions, shrimp farmers in Central America suffered a 75% drop in demand in all markets (national and international); this caused a severe overstocking of shrimp, which resulted in very high freezing costs, ultimately driving some producers to close operations until the market stabilized or directly out of business.

While most countries have re-opened their borders to trade and tourism, the impacts left by the lag on the transport and commercialization of inputs and outputs of the industry lingers. This is still observable in high production costs associated with very high freight and input prices and relatively low selling prices due to overstocking. Although this might be true for aquaculture as a whole, each species and region behaves differently. Shrimp, for example, has recovered (and even increased) their production when compared to pre-pandemic values. In July 2021, prices recovered with values reaching maximums observable over the last five years, and they have stabilized with smaller variations since then.

According to index-mundi, prices dropped 18% between April 2020 (avrg. USD 13.89 per kg, retail price in NY for headless shell on 26:30 caliber) and October that same year (avrg. USD 11.35 per kg, retail price), which matches the most significant part of the pandemic. Although the drop is steep, the reality is that shrimp prices are highly volatile, and this change might have other variables apart from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was more significant in those countries and species in which small and medium enterprises dominated, some of which were already under pressure for restricted access to inputs and cold storage systems, poor transportation infrastructure and systems, and underfinanced suppliers. In opposition, large-scale vertically integrated enterprises were able to keep or even increase production due to the control over inputs, storage, transport, and sale of their production, facilitating them to take over the market niche left by smaller enterprises.

Although it is true that the pandemic had severe impacts on most components of the aquaculture industry, not everything was a disaster. The pressure exerted on some producers pushed them towards creativity and innovation, looking into modernizing their infrastructure when possible, reducing some high costs, or taking the forced “time out” to improve their facilities or procedures. When it was impossible to improve infrastructure due to capital restrictions, other innovations surfaced, such as the search for new markets through e-commerce and home delivery, allowing a reduction in intermediary costs by taking closer the retail buyer to the farmer, benefiting both sides of the chain and reducing the under-stocking effect on retail markets. These innovations help consolidate the industry and improve the benefits of small-scale farmers, which appears to be something that will endure after the shock of the pandemic.

Even though it is true that the pandemic had severe impacts on most components of the aquaculture industry, not everything was a disaster. The pressure exerted on some producers pushed them towards creativity and innovation, looking into modernizing their infrastructure when possible, reducing some high costs, or taking the forced “time out” to improve their facilities or procedures. When it was impossible to improve infrastructure due to capital restrictions, other innovations surfaced, such as the search for new markets through e-commerce and home delivery, allowing a reduction in intermediary costs by taking closer the retail buyer to the farmer, benefiting both sides of the chain and reducing the under-stocking effect on retail markets. These innovations help consolidate the industry and improve the benefits of small-scale farmers, which appears to be something that will endure after the shock of the pandemic.

Apart from the severe direct impacts of the pandemic on the industry, another apparent problem observed was the dispersion, difficulty, and lag in the gathering and publication of data concerning this shock. Although this might seem trivial, the reality is that in order to produce significant insights into the impact and develop adequate public and private policies to mitigate the negative effects of the shock, it is of utmost importance to have public, transparent, and updated data. Most available production data has a two-year lag, meaning that right now, it is possible to start observing the numbers of the begging o the pandemic, but it is difficult to draw conclusions since there is no record for the broad public on the current status of the aquaculture industry, meaning that we can start analyzing and proposing some solutions once the acute part of the pandemic is over.

In our view, the pandemic left some interesting insights; the first one and common to all industries is the fragility of the globalized system. The large distances and complex logistic apparatus that concerns the transport of inputs and products from the industry showed the problematics that occur in the presence of a significant shock; this is important not only to the main production countries but more so to those that rely heavily on food imports since these are the ones that might see their population’s food safety in jeopardy.

Secondly, we saw that for aquaculture, being a primary production sector and therefore an “essential” sector, the pandemic had a small impact on the output; the problem was more on the distribution of said outputs and the costs and allocation of inputs and raw materials; hence we can confidently say that aquaculture is a very resilient industry.

Finally, we observed that severe changes and extreme shocks push producers to be innovative, generating new spaces for the industry, either in the form of new markets, better management practices, or innovative infrastructure. The producers that survive these shocks are those that can adapt to the changes or have the organization and means to assume the impacts of the shock, such as vertical integration.