Shrimp aquaculture management is tough. The farmer must ensure that the shrimps in the ponds are well fed, healthy, and in an environment that promotes growth. This might seem easy to a non farmer, I mean, how difficult can it be to keep some shrimp alive? Well, the answer might be much more complicated than the question suggest.

Shrimp farmers must account for all the factors that affect production; a bad decision can cost them thousands or even millions of dollars. Furthermore, there are a lot of decisions to make: the density of production, the proportion of feed given, to use or not partial harvests, the use of treatments, chemicals, probiotics, antibiotics or vitamins, the response to the presence of pathogens and the health of the product overall, the water quality (temperature, oxygen, dissolved ammonia, salinity, pH…), and, among others, when to harvest.

On top of all the points mentioned above, the extension of the farms makes extremely difficult to manage and to manually gather data continuously, which exacerbates the difficulty of the task. Finally, once a farmer managed to control all the physicochemical and biological aspects of production, there is still one more mountain to climb: the market.

The shrimp market

The term “shrimp” includes a lot of species and, in some cases, with differentiated markets. Nonetheless, most of them share most market characteristics and, except on some cases, can be considered substitute products, therefore, we will use the term “shrimp” to reference all the different species that compose this group.

In most cases, shrimp farmers are what in economics is known a price-takers. That means that, since there is a lot of production worldwide and because the price of the product is dictated by the balance between supply and demand, the presence/absence of your production is so small that it does not affect the availability of the product, hence it does not influence the price. Nonetheless, the fact that production costs and quantity, quality, and demand are very fluctuating, coupled with the massive effect that an epidemiological outbreak can have (as was the WSSD or EMS), global prices tend to variate highly.

Shrimp is considered a high value group of species, with first sale prices fluctuating roughly between 3 and 7 USD per kg, which is high compared to other seafood products, like tilapia which ranges around 1.5 and 2.5 USD per kg. This alone is a major incentive for farmers to choose shrimp instead of other species. But observe the difference between the low and high shrimp prices, there is a 4 USD difference, that is a 133% value increase respect to the low price. That means that regardless of the quantity produced, if you sell your product in a low-price period, this could impact the income and therefore the revenue generated by the farm.

Furthermore, shrimp prices have a gauge scale, with higher prices for bigger shrimp and lower prices for smaller ones. this aspect of the market begs the question how long should I keep my shrimp in the pond? even more relevant.

This market trends are what, most of the times, dictate if a farm will sell its product. If the farmers do not have the infrastructure to freeze and conserve the product, they must sell immediately after harvest, which then plays a major role in the decision of when to harvest.

In addition to the selling price of shrimp, there is another market indicator that will determine the success or failure of a production cycle, that is the production costs. Production costs are the sum of the costs associated to the production of shrimp. They can be fixed (when the cost is independent to the quantity produced), or variable (when the cost depends on the amount of shrimp produced). Of all costs, the most significant one in most shrimp farms is feed, which can represent up to 65% of the total.

Marine shrimp are omnivores, but current aquafeed technology presents some advantages for the feed that is produced with protein that comes from an animal source. Today, most commercial feed for shrimp is produced with a significant component of fishmeal. Apart from shrimp, fishmeal is an important ingredient in all aquafeed produced for carnivorous species, which makes this ingredient a highly wanted product worldwide. Fishmeal comes, mostly, from reduction fisheries, which have a production maximum set by the capacity of the natural stock to recover from the fishing activity. Therefore, this product has experienced an increase in demand associated to aquaculture growth, and supply has been staggered for decades. This balance has been translated in price increases, which directly affect the production costs of shrimp.

Therefore, we can conclude that the more feed we provide, the higher the production costs. But feed is the “fuel” of growth, so if we do not provide enough, growth will be deficient, decreasing biomass over time faster and, therefore, increasing unit production costs or even making the farm unprofitable.

Biological aspects of the harvest decision

We’ve seen that the amount of feed is one of the key aspects that determine the success of a shrimp farm. But it is not the only one. Let’s remember that shrimp biomass (B) is a function of weight (W), number of organisms (N) and time (t). These three aspects will determine the biological performance of a farm.

Bt=NtWt

One common flaw among shrimp farmers is to assume that shrimp grow in a “grams per week” bases. The error here is not that they don’t achieve this growth during the first period of production, but assuming they can keep it up in a sustained way over time. Thinking like this is assuming that the organisms have a linear growth. This assumption can lead us to overestimate the productivity of a pond. Furthermore, it can lead to losses due to overfeeding.

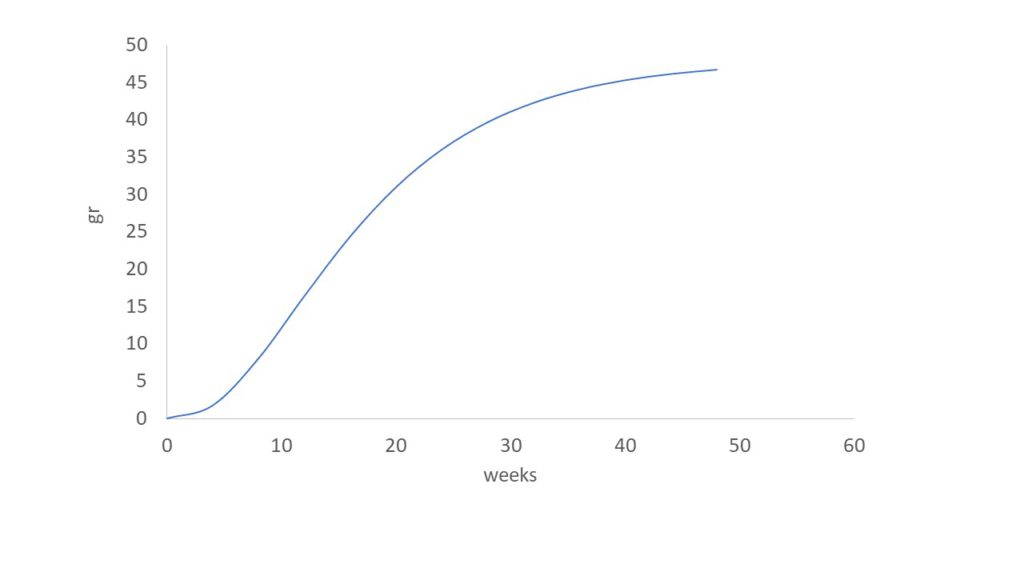

Shrimp, as well as most aquaculture organisms, do not follow a linear growth, instead, they have a logistical behavior (see image below). This might seem like a trivial thing when observed in a per organism bases; I mean, it looks almost linear, and they keep growing, which will lead to a higher price so, why not keep them in the pond?

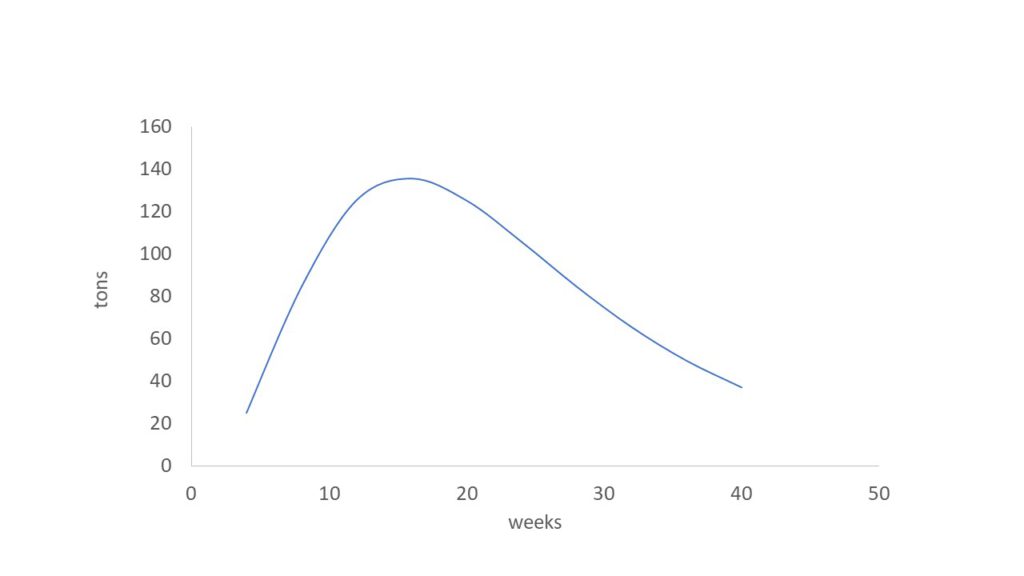

The effect of the sigmoidal growth is better grasped when accounting for its impact on the full production cycle, that also includes the effect for mortality over time. This growth behavior can severely impact biomass in a tank.

Ok, then the answer seems pretty easy, we must harvest when the biomass is in its highest, right? Well, not necessarily, there is one more aspect that needs to be accounted for, which is the economic performance of our farm.

Economic aspects of the harvest decision

We have broadly covered the market aspects of shrimp, now is time to deepen in the microeconomic aspects of our farm, which will be crucial to select a better harvest time.

The economic aspects of a farm are particular to each facility depending on their methods, infrastructure, policy, distributors, labor costs, debt, energy use and costs, feed use and costs, technologies, etc. To effectively answer the question of when’s the best time to harvest to maximize profits, we will use a marginal approach. For this, its necessary to know the cost structure and function of the farm.

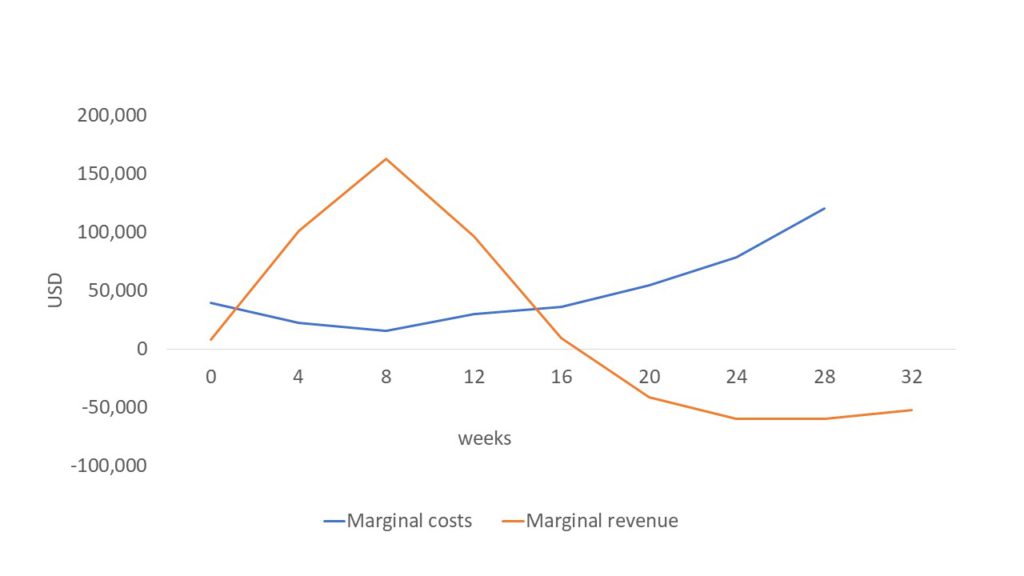

According to the rule for optimal harvesting, the shrimp must be harvested when the marginal increase in the value of the capital (i.e., shrimp in ponds) equals the opportunity cost.

In other words, the optimal time for harvest is the point where the marginal revenue equals the marginal cost of operation. In this case, both marginal revenue and marginal costs are determined by time since time affects biomass, price, and operational costs. As shown in the example below optimal harvest for this particular farm would be before the 8th month, which a couple of days before reaching the highest biomass in pond. Of course, this result depends on feed price, FCR, growth, mortality, selling price, etc.

Observe that, in this example, optimal harvest occurs when individual weight is around 23 gr, that is a 15-20 caliber (around 9.3 USD per kg, retail price), and not when shrimp are at their highest weight, which would be around 46 grams, that is a U10 caliber (around 10.8 USD per kg, retail price). Furthermore, optimal harvest occurs a week before obtaining maximum biomass, since FCR start do decrease.

This simple analysis can be enriched with some other aspects of production, like the heterogeneity of growth, the use of partial harvests and its impact on density-dependant species, the effect of the markets, accounting for price fluctuations, and other factors pertinent to production. Models can be as sophisticated as necessary, and they have proven to be a powerful tool to improve aquaculture management.

If you would like to discuss this approach or require assistance with this analysis, please reach out via our online community at https://community.shrimpstar.com/